History of cinema in India

The history of cinema in India extends to the beginning of the film era. Following the screening of the Lumière and Robert Paul moving pictures in London in 1896, commercial cinematography became a worldwide sensation and these films were shown in Bombay (now Mumbai) that same year.[1]

Silent era (1890s–1920s)

[edit]In 1897, a film presentation by filmmaker Professor Stevenson featured a stage show at Calcutta's Star Theatre. With Stevenson's camera and encouragement, Indian photographer Hiralal Sen filmed scenes from that show, exhibited as The Flower of Persia (1898).[2] The Wrestlers (1899), by H. S. Bhatavdekar, showing a wrestling match at the Hanging Gardens in Bombay, was the first film to be shot by an Indian and the first Indian documentary film.[citation needed] From 1913 to 1931, all the movies made in India were silent films, which had no sound and had intertitles.[3]

|

|

|

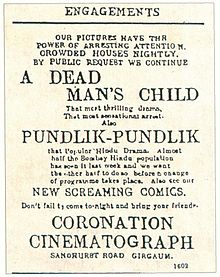

In 1913, Dadasaheb Phalke released Raja Harishchandra (1913) in Bombay, the first film made in India. It was a silent film incorporating Marathi and English intertitles.[8] It was premiered in Coronation cinema in Girgaon.[9]

Although some claim Shree Pundalik (1912) of Dadasaheb Torne is the first ever film made in India.[10][11][9] Some film scholars have argued that Pundalik was not a true Indian film because it was simply a recording of a stage play, filmed by a British cameraman and it was processed in London.[12][13][8] Raja Harishchandra of Phalke had a story based on Hindu Sanskrit legend of Harishchandra, a truthful King and its success led many to consider him a pioneer of Indian cinema.[9] Phalke used an all Indian crew including actors Anna Salunke and D. D. Dabke. He directed, edited, processed the film himself.[8] Phalke saw The Life of Christ (1906) by the French director Alice Guy-Blaché, While watching Jesus on the screen, Phalke envisioned Hindu deities Rama and Krishna instead and decided to start in the business of "moving pictures".[14]

In South India, film pioneer Raghupathi Venkaiah Naidu, credited as the father of Telugu cinema, built the first cinemas in Madras (now Chennai), and a film studio was established in the city by Nataraja Mudaliar.[15][16][17] In 1921, Naidu produced the silent film, Bhishma Pratigna, generally considered to be the first Telugu feature film.[18]

The first Tamil and Malayalam films, also silent films, were Keechaka Vadham (1917–1918, R. Nataraja Mudaliar)[19] and Vigathakumaran (1928, J. C. Daniel Nadar). The latter was the first Indian social drama film and featured the first Dalit-caste film actress.[citation needed]

The first chain of Indian cinemas, Madan Theatre, was owned by Parsi entrepreneur Jamshedji Framji Madan, who oversaw the production and distribution of films for the chain.[9] These included film adaptations from Bengal's popular literature and Satyawadi Raja Harishchandra (1917), a remake of Phalke's influential film.[citation needed]

Films steadily gained popularity across India as affordable entertainment for the masses (admission as low as an anna [one-sixteenth of a rupee] in Bombay).[1] Young producers began to incorporate elements of Indian social life and culture into cinema, others brought new ideas from across the world. Global audiences and markets soon became aware of India's film industry.[20]

In 1927, the British government, to promote the market in India for British films over American ones, formed the Indian Cinematograph Enquiry Committee. The ICC consisted of three British and three Indians, led by T. Rangachari, a Madras lawyer.[21] This committee failed to bolster the desired recommendations of supporting British Film, instead recommending support for the fledgling Indian film industry, and their suggestions were set aside.

Sound era (1930s)

[edit]The first Indian sound film was Alam Ara (1931) made by Ardeshir Irani.[9] Ayodhyecha Raja (1932) was the first sound film of Marathi cinema.[3] Irani also produced South India's first sound film, the Tamil–Telugu bilingual talking picture Kalidas (1931, H. M. Reddy).[22]

The first Telugu film with audible dialogue, Bhakta Prahlada (1932), was directed by H. M. Reddy, who directed the first bilingual (Telugu and Tamil) talkie Kalidas (1931).[23] East India Film Company produced its first Telugu film, Savitri (1933, C. Pullayya), adapted from a stage play by Mylavaram Bala Bharathi Samajam.[24] The film received an honorary diploma at the 2nd Venice International Film Festival.[25] Chittoor Nagayya was one of the first multilingual filmmakers in India.[26][27]

Jumai Shasthi was the first Bengali short film as a talkie.[28]

Jyoti Prasad Agarwala made his first film Joymoti (1935) in Assamese, and later made Indramalati.[citation needed] The first film studio in South India, Durga Cinetone, was built in 1936 by Nidamarthi Surayya in Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh.[29][contradictory] The advent of sound to Indian cinema launched musicals such as Indra Sabha and Devi Devyani, marking the beginning of song-and-dance in Indian films.[9] By 1935, studios emerged in major cities such as Madras, Calcutta and Bombay as filmmaking became an established industry, exemplified by the success of Devdas (1935).[30] The first colour film made in India was Kisan Kanya (1937, Moti B).[31] Viswa Mohini (1940) was the first Indian film to depict the Indian movie-making world.[32]

Swamikannu Vincent, who had built the first cinema of South India in Coimbatore, introduced the concept of "tent cinema" in which a tent was erected on a stretch of open land to screen films. The first of its kind was in Madras and called Edison's Grand Cinema Megaphone. This was due to the fact that electric carbons were used for motion picture projectors.[33][further explanation needed] Bombay Talkies opened in 1934 and Prabhat Studios in Pune began production of Marathi films.[30] Sant Tukaram (1936) was the first Indian film to be screened at an international film festival,[contradictory] at the 1937 edition of the Venice Film Festival. The film was judged one of the three best films of the year.[34] However, while Indian filmmakers sought to tell important stories, the British Raj banned Wrath (1930) and Raithu Bidda (1938) for broaching the subject of the Indian independence movement.[9][35][36]

The Indian Masala film—a term used for mixed-genre films that combined song, dance, romance, etc.—arose following the Second World War.[30] During the 1940s, cinema in South India accounted for nearly half of India's cinema halls, and cinema came to be viewed as an instrument of cultural revival.[30] The Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA), an art movement with a communist inclination, began to take shape through the 1940s and the 1950s.[37] IPTA plays, such as Nabanna (1944), prepared the ground for realism in Indian cinema, exemplified by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas's Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth, 1946).[37] The IPTA movement continued to emphasise realism in films Mother India (1957) and Pyaasa (1957), among India's most recognisable cinematic productions.[38]

Following independence, the 1947 partition of India divided the nation's assets and a number of studios moved to Pakistan.[30] Partition became an enduring film subject thereafter.[30] The Indian government had established a Films Division by 1948, which eventually became one of the world's largest documentary film producers with an annual production of over 200 short documentaries, each released in 18 languages with 9,000 prints for permanent film theatres across the country.[39]

Golden Age (late 1940s–1960s)

[edit]

The period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s is regarded by film historians as the Golden Age of Indian cinema.[43][44][45] This period saw the emergence of the parallel cinema movement, which emphasised social realism. Mainly led by Bengalis,[46] early examples include Dharti Ke Lal (1946, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas),[47] Neecha Nagar (1946, Chetan Anand),[48] Nagarik (1952, Ritwik Ghatak)[49][50] and Do Bigha Zamin (1953, Bimal Roy), laying the foundations for Indian neorealism[51]

The Apu Trilogy (1955–1959, Satyajit Ray) won prizes at several major international film festivals and firmly established the parallel cinema movement.[52] It was influential on world cinema and led to a rush of coming-of-age films in art house theatres.[53] Cinematographer Subrata Mitra developed the technique of bounce lighting, to recreate the effect of daylight on sets, during the second film of the trilogy[54] and later pioneered other effects such as the photo-negative flashbacks and X-ray digressions.[55]

During the 1950s, Indian cinema reportedly became the world's second largest film industry, earning a gross annual income of ₹250 million (equivalent to ₹26 billion or US$320 million in 2023) in 1953.[56] The government created the Film Finance Corporation (FFC) in 1960 to provide financial support to filmmakers.[57] While serving as Information and Broadcasting Minister of India in the 1960s, Indira Gandhi supported the production of off-beat cinema through the FFC.[57]

Baburao Patel of Filmindia called B. N. Reddy's Malliswari (1951) an "inspiring motion picture" which would "save us the blush when compared with the best of motion pictures of the world".[58] Film historian Randor Guy called Malliswari scripted by Devulapalli Krishnasastri a "poem in celluloid, told with rare artistic finesse, which lingers long in the memory".[59]

Commercial Hindi cinema began thriving, including acclaimed films Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959, Guru Dutt) Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955, Raj Kapoor). These films expressed social themes mainly dealing with working-class urban life in India; Awaara presented Bombay as both a nightmare and a dream, while Pyaasa critiqued the unreality of city life.[46]

Epic film Mother India (1957, Mehboob Khan) was the first Indian film to be nominated for the US-based Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences' Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film[citation needed] and defined the conventions of Hindi cinema for decades.[60][61][62] It spawned a new genre of dacoit films.[63] Gunga Jumna (1961, Dilip Kumar) was a dacoit crime drama about two brothers on opposite sides of the law, a theme that became common in Indian films in the 1970s.[64] Madhumati (1958, Bimal Roy) popularised the theme of reincarnation in Western popular culture.[65]

Actor Dilip Kumar rose to fame in the 1950s, and was the biggest Indian movie star of the time.[66][67] He was a pioneer of method acting, predating Hollywood method actors such as Marlon Brando. Much like Brando's influence on New Hollywood actors, Kumar inspired Hindi actors, including Amitabh Bachchan, Naseeruddin Shah, Shah Rukh Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui.[68]

Neecha Nagar (1946) won the Palme d'Or at Cannes[48] and Indian films competed for the award most years in the 1950s and early 1960s.[citation needed] Ray is regarded as one of the greatest auteurs of 20th century cinema,[69] along with his contemporaries Dutt[70] and Ghatak.[71] In 1992, the Sight & Sound Critics' Poll ranked Ray at No. 7 in its list of Top 10 Directors of all time.[72] Multiple films from this era are included among the greatest films of all time in various critics' and directors' polls, including The Apu Trilogy,[73] Jalsaghar, Charulata[74] Aranyer Din Ratri,[75] Pyaasa, Kaagaz Ke Phool, Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar, Awaara, Baiju Bawra, Mother India, Mughal-e-Azam[76] and Subarnarekha (also tied at No. 11).[71]

Sivaji Ganesan became India's first actor to receive an international award when he won the Best Actor award at the Afro-Asian film festival in 1960 and was awarded the title of Chevalier in the Legion of Honour by the French Government in 1995.[77] Tamil cinema is influenced by Dravidian politics,[78] with prominent film personalities C N Annadurai, M G Ramachandran, M Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa becoming Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu.[79][timeframe?]

Post 1970s: The Modern Era

[edit]By 1986, India's annual film output had increased to 833 films annually, making India the world's largest film producer.[80] Hindi film production of Bombay, the largest segment of the industry, became known as "Bollywood".

Summary of the 2022 box office revenues.

By 1996, the Indian film industry had an estimated domestic cinema viewership of 600 million people, establishing India as one of the largest film markets, with the largest regional industries being Hindi, Telugu, and Tamil films.[81] In 2001, in terms of ticket sales, Indian cinema sold an estimated 3.6 billion tickets annually across the globe, compared to Hollywood's 2.6 billion tickets sold.[82][83]

Hindi

[edit]Realistic parallel cinema continued throughout the 1970s,[84] practised in many Indian film cultures. The FFC's art film orientation came under criticism during a Committee on Public Undertakings investigation in 1976, which accused the body of not doing enough to encourage commercial cinema.[85]

Hindi commercial cinema continued with films such as Aradhana (1969), Sachaa Jhutha (1970), Haathi Mere Saathi (1971), Anand (1971), Kati Patang (1971) Amar Prem (1972), Dushman (1972) and Daag (1973).[importance?]

By the early 1970s, Hindi cinema was experiencing thematic stagnation,[88] dominated by musical romance films.[89] Screenwriter duo Salim–Javed (Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar) revitalised the industry.[88] They established the genre of gritty, violent, Bombay underworld crime films with Zanjeer (1973) and Deewaar (1975).[90][91] They reinterpreted the rural themes of Mother India and Gunga Jumna in an urban context reflecting 1970s India,[88][92] channelling the growing discontent and disillusionment among the masses,[88] unprecedented growth of slums[93] and urban poverty, corruption and crime,[94] as well as anti-establishment themes.[95] This resulted in their creation of the "angry young man", personified by Amitabh Bachchan,[95] who reinterpreted Kumar's performance in Gunga Jumna[88][92] and gave a voice to the urban poor.[93]

By the mid-1970s, Bachchan's position as a lead actor was solidified by crime-action films Zanjeer and Sholay (1975).[85] He emerged as the most popular and significant star in India in 1970s onwards. The devotional classic Jai Santoshi Ma (1975) was made on a low budget and became a box office success and a cult classic.[85] Another important film was Deewaar (1975, Yash Chopra),[64] a crime film with brothers on opposite sides of the law which Danny Boyle described as "absolutely key to Indian cinema".[96]

The term "Bollywood" was coined in the 1970s,[97][98] when the conventions of commercial Bombay-produced Hindi films were established.[99] Key to this was Nasir Hussain and Salim–Javed's creation of the masala film genre, which combines elements of action, comedy, romance, drama, melodrama and musical.[99][100] Their film Yaadon Ki Baarat (1973) has been identified as the first masala film and the first quintessentially Bollywood film.[99][101] Masala films made Bachchan the biggest Bollywood movie star of the period. Another landmark was Amar Akbar Anthony (1977, Manmohan Desai).[101][102] Desai further expanded the genre in the 1970s and 1980s.

Commercial Hindi cinema grew in the 1980s, with films such as Ek Duuje Ke Liye (1981), Disco Dancer (1982), Himmatwala (1983), Tohfa (1984), Naam (1986), Mr India (1987), and Tezaab (1988).

In the late 1980s,[timeframe?] Hindi cinema experienced another period of stagnation, with a decline in box office turnout, due to increasing violence, decline in musical melodic quality, and rise in video piracy, leading to middle-class family audiences abandoning theatres. The turning point came with Indian blockbuster Disco Dancer (1982) which began the era of disco music in Indian cinema. Lead actor Mithun Chakraborty and music director Bappi Lahiri had the highest number of mainstream Indian hit movies that decade. At the end of the decade, Yash Chopra's Chandni (1989) created a new formula for Bollywood musical romance films, reviving the genre and defining Hindi cinema in the years that followed.[103][104] Commercial Hindi cinema grew in the late 1980s and 1990s, with the release of Mr. India (1987), Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), Chaalbaaz (1989), Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Lamhe (1991), Saajan (1991), Khuda Gawah (1992), Khalnayak (1993), Darr (1993),[85] Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994), Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995), Dil To Pagal Hai (1997), Pyar Kiya Toh Darna Kya (1998) and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998). Cult classic Bandit Queen (1994) directed by Shekhar Kapur received international recognition and controversy.[105][106]

In the late 1990s, there was a resurgence of parallel cinema in Bollywood, largely due to the critical and commercial success of crime films such as Satya (1998) and Vaastav (1999). These films launched a genre known as "Mumbai noir",[108] reflecting social problems in the city.[109] Ram Gopal Varma directed the Indian Political Trilogy, and the Indian Gangster Trilogy; film critic Rajeev Masand had labelled the latter series as one of the "most influential movies of Bollywood.[110][111][112] The first instalment of the trilogy, Satya, was also listed in CNN-IBN's 100 greatest Indian films of all time.[113]

Since the 1990s, the three biggest Bollywood movie stars have been the "Three Khans": Aamir Khan, Shah Rukh Khan, and Salman Khan.[114][115] Combined, they starred in the top ten highest-grossing Bollywood films,[114] and have dominated the Indian box office since the 1990s.[116][117] Shah Rukh Khan was the most successful for most of the 1990s and 2000s, while Aamir Khan has been the most successful since the late 2000s;[118] according to Forbes, Shah Rukh Khan is "arguably the world's biggest movie star" as of 2017, due to his immense popularity in India and China.[119] Other notable Hindi film stars of recent decades include Arjun Rampal, Sunny Deol, Akshay Kumar, Ajay Devgn, Hrithik Roshan, Anil Kapoor, Sanjay Dutt, Sridevi, Madhuri Dixit, Juhi Chawla, Karisma Kapoor, Kajol, Tabu, Aishwarya Rai, Rani Mukerji and Preity Zinta.

Haider (2014, Vishal Bhardwaj), the third instalment of the Indian Shakespearean Trilogy after Maqbool (2003) and Omkara (2006),[120] The 2000s and 2010s also saw the rise of a new generation of popular actors like Shahid Kapoor, Ranbir Kapoor, Ranveer Singh, Ayushmann Khurrana, Varun Dhawan, Sidharth Malhotra, Sushant Singh Rajput, Kartik Aaryan, Arjun Kapoor, Aditya Roy Kapur and Tiger Shroff, as well as actresses like Vidya Balan, Priyanka Chopra, Kareena Kapoor, Katrina Kaif, Kangana Ranaut, Deepika Padukone, Sonam Kapoor, Anushka Sharma, Shraddha Kapoor, Alia Bhatt, Parineeti Chopra and Kriti Sanon with Balan, Ranaut and Bhatt gaining wide recognition for successful female-centric films such as The Dirty Picture (2011), Kahaani (2012), Queen (2014), Highway (2014), Tanu Weds Manu Returns (2015), Raazi (2018) and Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022).

Salim–Javed were highly influential in South Indian cinema. In addition to writing two Kannada films, many of their Bollywood films had remakes produced in other regions, including Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam cinema. While the Bollywood directors and producers held the rights to their films in Northern India, Salim–Javed retained the rights in South India, where they sold remake rights for films such as Zanjeer, Yaadon Ki Baarat and Don.[121] Several of these remakes became breakthroughs for actor Rajinikanth.[89][122]

Sridevi is widely regarded as the first female superstar of Indian cinema due to her pan-Indian appeal with equally successful careers in Hindi, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada and Telugu cinema. She is the only Bollywood actor to have starred in a top 10 grossing film each year of her active career (1983–1997).[citation needed]

Telugu

[edit]K. V. Reddy's Mayabazar (1957) is a landmark film in Indian cinema, a classic of Telugu cinema that inspired generations of filmmakers. It blends myth, fantasy, romance and humour in a timeless story, captivating audiences with its fantastical elements. The film excelled in various departments like cast performances, production design, music, cinematography and is particularly revered for its use of technology.[123][124] The use of special effects, innovative for the 1950s, like the first illusion of moonlight, showcased technical brilliance.. Powerful performances and relatable themes ensure Mayabazar stays relevant, a classic enjoyed by new generations. On the centenary of Indian cinema in 2013, CNN-IBN included Mayabazar in its list of "100 greatest Indian films of all time".[125] In a poll conducted by CNN-IBN among those 100 films, Mayabazar was voted by the public as the "Greatest Indian film of all time."[126]

K. Viswanath, one of the prominent auteurs of Indian cinema, he received international recognition for his works, and is known for blending parallel cinema with mainstream cinema. His works such as Sankarabharanam (1980) about revitalisation of Indian classical music won the "Prize of the Public" at the Besançon Film Festival of France in the year 1981.[127] Forbes included J. V. Somayajulu's performance in the film on its list of "25 Greatest Acting Performances of Indian Cinema".[128] Swathi Muthyam (1986) was India's official entry to the 59th Academy Awards.[127] Swarna Kamalam (1988) the dance film choreographed by Kelucharan Mohapatra, and Sharon Lowen was featured at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, fetching three Indian Express Awards.[129][130]

B. Narsing Rao, K. N. T. Sastry, and A. Kutumba Rao garnered international recognition for their works in new-wave cinema.[131][132] Narsing Rao's Maa Ooru (1992) won the "Media Wave Award" of Hungary; Daasi (1988) and Matti Manushulu (1990) won the Diploma of Merit awards at the 16th and 17th MIFF respectively.[133][134][135] Sastry's Thilaadanam (2000) received "New Currents Award" at the 7th Busan;[136][137] Rajnesh Domalpalli's Vanaja (2006) won "Best First Feature Award" at the 57th Berlinale.[138][139]

Ram Gopal Varma's Siva (1989), which attained cult following[140] introduced steadicams and new sound recording techniques to Indian films.[141] Siva attracted the young audience during its theatrical run, and its success encouraged filmmakers to explore a variety of themes and make experimental films.[142] Varma introduced road movie and film noir to Indian screen with Kshana Kshanam (1991).[143] Varma experimented with close-to-life performances by the lead actors, which bought a rather fictional storyline a sense of authenticity at a time when the industry was being filled with commercial fillers.[144]

Singeetam Srinivasa Rao introduced time travel to the Indian screen with Aditya 369 (1991). The film dealt with exploratory dystopian and apocalyptic themes, taking the audience through a post-apocalyptic experience via time travel and folklore from 1526 CE, including a romantic subplot.[145] Singeetam Srinivasa Rao was inspired by the classic sci-fi novel The Time Machine.[146][147][148]

Chiranjeevi's works such as the social drama film Swayamkrushi (1987), comedy thriller Chantabbai (1986), the vigilante thriller Kondaveeti Donga (1990),[149] the Western thriller Kodama Simham (1990), and the action thriller, Gang Leader (1991), popularised genre films with the highest estimated cinema footfalls.[150] Sekhar Kammula's Dollar Dreams (2000), which explored the conflict between American dreams and human feelings, re-introduced social realism to Telugu film which had stagnated in formulaic commercialism.[151] War drama Kanche (2015, Krish Jagarlamudi) explored the 1944 Nazi attack on the Indian army in the Italian campaign of the Second World War.[152]

Pan-Indian film is a term related to Indian cinema that originated with Telugu cinema as a mainstream commercial film appealing to audiences across the country with a spread to world markets.[155] S. S. Rajamouli pioneered the pan-Indian films movement with duology of epic action films Baahubali: The Beginning (2015) and Baahubali 2: The Conclusion (2017), that changed the face of Indian cinema. Baahubali: The Beginning became the first Indian film to be nominated for American Saturn Awards.[156] It received national and international acclaim for Rajamouli's direction, story, visual effects, cinematography, themes, action sequences, music, and performances, and became a record-breaking box office success.[157] The sequel Baahubali 2 (2017) went on to win the American "Saturn Award for Best International Film" & emerged as the second-highest-grossing Indian film of all time.[158][159]

S.S Rajamouli followed up with the alternate historical film RRR (2022) that received universal critical acclaim for its direction, screenwriting, cast performances, cinematography, soundtrack, action sequences and VFX, which further consolidated the Pan-Indian film market. The film was considered one of the ten best films of the year by the National Board of Review, making it only the seventh non-English language film ever to make it to the list.[160] It also became the first Indian film by an Indian production to win an Academy Award.[161] The film went on to receive several other nominations at the Golden Globe Awards, Critics' Choice Movie Award including Best Foreign Language Film.[162] Films like Pushpa: The Rise, Salaar: Part 1 – Ceasefire and Kalki 2898 AD have further contributed to the pan-Indian film wave.

Actors like Prabhas, Allu Arjun, Ram Charan and N. T. Rama Rao Jr. enjoy a nationwide popularity among the audiences after the release of their respective Pan-Indian films. Film critics, journalists and analysts, such as Baradwaj Rangan and Vishal Menon, have labelled Prabhas as the "first legit Pan-Indian Superstar".[163]

Hindi cinema has been remaking Telugu films since the late 1940s, some of which went on to become landmark films. Between 2000 and 2019, one in every three successful films made in Hindi was either a remake or part of a series. And most of the star actors, have starred in the hit remakes of Telugu films.[164]

Tamil

[edit]Tamil cinema established Madras (now Chennai) as a secondary film production centre in India, used by Hindi cinema, other South Indian film industries, and Sri Lankan cinema.[165] Over the last quarter of the 20th century, Tamil films from India established a global presence through distribution to an increasing number of overseas theatres.[166][167] The industry also inspired independent filmmaking in Sri Lanka and Tamil diaspora populations in Malaysia, Singapore, and the Western Hemisphere.[168]

Marupakkam (1991, K. S. Sethumadhavan) and Kanchivaram (2007) each won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film.[169] Tamil films receive significant patronage in neighbouring Indian states Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat and New Delhi. In Kerala and Karnataka the films are directly released in Tamil but in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana they are generally dubbed into Telugu.[170][171]

Tamil films have had international success for decades. Since Chandralekha (1948), Muthu (1995) was the second Tamil film to be dubbed into Japanese (as Mutu: Odoru Maharaja[172]) and grossed a record $1.6 million in 1998.[173] In 2010, Enthiran grossed a record $4 million in North America.[174] Tamil-language films appeared at multiple film festivals. Kannathil Muthamittal (Ratnam), Veyyil (Vasanthabalan) and Paruthiveeran (Ameer Sultan), Kanchivaram (Priyadarshan) premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. Tamil films were submitted by India for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film on eight occasions.[175] Chennai-based music composer A. R. Rahaman achieved global recognition with two Academy Awards and is nicknamed as "Isai Puyal" (musical storm) and "Mozart of Madras". Nayakan (1987, Kamal Haasan) was included in Time's All-Time 100 Movies list.[176]

Malayalam

[edit]

Malayalam cinema experienced its Golden Age during this time with works of filmmakers such as Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Aravindan, T. V. Chandran and Shaji N. Karun.[177] Gopalakrishnan is often considered to be Ray's spiritual heir.[178] He directed some of his most acclaimed films during this period, including Elippathayam (1981) which won the Sutherland Trophy at the London Film Festival.[citation needed] In 1984 My Dear Kuttichathan, directed by Jijo Punnoose under Navodaya Studio, was released and it was the first Indian film to be filmed in 3D format. Karun's debut film Piravi (1989) won the Caméra d'Or at Cannes, while his second film Swaham (1994) was in competition for the Palme d'Or. Vanaprastham was screened at the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Film Festival.[citation needed] Murali Nair's Marana Simhasanam (1999), inspired by the first execution by electrocution in India, the film was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival where it won the Caméra d'Or.[179][180] The film received special reception at the British Film Institute.[181][182]

Fazil's Manichitrathazhu (1993), scripted by Madhu Muttam, is inspired by a tragedy that happened in an Ezhava tharavad of Alummoottil meda' (an old traditional house) located at Muttom, Alappuzha district, with a central Travancore Channar family, in the 19th century.[183] It was remade in four languages – in Kannada as Apthamitra, in Tamil as Chandramukhi , in Bengali as Rajmohol and in Hindi as Bhool Bhulaiyaa – all being commercially successful.[184] Jeethu Joseph's Drishyam (2013) was remade into four other Indian languages: Drishya (2014) in Kannada, Drushyam (2014) in Telugu, Papanasam (2015) in Tamil and Drishyam (2015) in Hindi. Internationally, it was remade in Sinhala language as Dharmayuddhaya (2017) and in Chinese as Sheep Without a Shepherd (2019), and also in Indonesian.[185][186][187]

Kannada

[edit]Ethnographic works took prominence such as B. V. Karanth's Chomana Dudi (1975), (based on Chomana Dudi by Shivaram Karanth), Girish Karnad's Kaadu (1973), (based on Kaadu by Srikrishna Alanahalli), Pattabhirama Reddy's Samskara (1970) (based on Samskara by U. R. Ananthamurthy), fetching the Bronze Leopard at Locarno International Film Festival,[188] and T. S. Nagabharana's Mysuru Mallige (based on the works of poet K. S. Narasimhaswamy).[189] Girish Kasaravalli's Ghatashraddha (1977), won the Ducats Award at the Manneham Film Festival Germany,[190] Dweepa (2002), made to Best Film at Moscow International Film Festival,[191][192]

Prashanth Neel's K.G.F (2018, 2022) is a period action series based on the Kolar Gold Fields.[193] Set in the late 1970s and early 1980s the series follows Raja Krishnappa Bairya aka Rocky (Yash), a Mumbai-based high ranking mercenary born in poverty, to his rise to power in the Kolar Gold Fields and the subsequent uprising as one of the biggest gangster and businessman at that time.[194][195] The film gathered cult following becoming the highest-grossing Kannada film.[196] Rishab Shetty's Kantara (2022), received acclaim for showcasing the Bhoota Kola, a native Ceremonial dance performance prevalent among the Hindus of coastal Karnataka.[197]

Marathi

[edit]Marathi cinema also known as Marathi film industry, is a film industry based in Mumbai, Maharashtra. It is the oldest film industry of India. The first Marathi movie, Raja Harishchandra of Dadasaheb Phalke was made in 1912, released in 1913 in Girgaon, it was a silent film with Marathi-English intertitles made with full Marathi actors and crew, after the film emerged successful, Phalke made many movies on Hindu mythology.

In 1932, the first sound film, Ayodhyecha Raja was released, just five years after 1st Hollywood sound film The Jazz Singer (1927). The first Marathi film in colour, Pinjara (1972), was made by V. Shantaram. In 1960s–70s movies was based on rural, social subjects with drama and humour genre, Nilu Phule was prominent villain that time. In 1980s, M. Kothare and Sachin Pilgaonkar made many hit movies on thriller, and comedy genre respectively. Ashok Saraf and Laxmikant Berde starred in many of these and emerged as top actors. Mid-2000s onwards, the industry frequently made hit movies.[3][8][198]

See also

[edit]- Film history

- List of Indian male film actors

- List of Indian film actresses

- List of Indian film directors

References

[edit]- ^ a b Burra & Rao, 252

- ^ McKernan, Luke (31 December 1996). "Hiralal Sen (copyright British Film Institute)". Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- ^ a b c "First Indian talkie film Alam Ara was released on this day: Top silent era films". India Today. 14 March 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Dadasaheb Phalke Father of Indian Cinema". Thecolorsofindia.com. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Bāpū Vāṭave; National Book Trust (2004). Dadasaheb Phalke, the father of Indian cinema. National Book Trust. ISBN 978-81-237-4319-6. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Sachin Sharma (28 June 2012). "Godhra forgets its days spent with Dadasaheb Phalke". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Vilanilam, J. V. (2005). Mass Communication in India: A Sociological Perspective. New Delhi: Sage Publications. p. 128. ISBN 81-7829-515-6.

- ^ a b c d Bose, Ishani (21 November 2013). "Dadasaheb Torne, not Dadasaheb Phalke, was pioneer of Indian Cinema". DNA. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Burra & Rao, 253

- ^ Kadam, Kumar (24 April 2012). "दादासाहेब तोरणेंचे विस्मरण नको!". Maharashtra Times. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- ^ Raghavendara, MK (5 May 2012). "What a journey".

- ^ Damle, Manjiri (21 April 2012). "Torne's 'Pundlik' came first, but missed honour". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013.

- ^ Mishra, Garima (3 May 2012). "Bid to get Pundalik recognition as first Indian feature film".

- ^ Dharap, B. V. (1985). Indian films. National Film Archive of India. p. 35.

- ^ "Nijam cheppamantara, abaddham cheppamantara..." The Hindu. 9 February 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2020 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ Velayutham, Selvaraj. Tamil cinema: the cultural politics of India's other film industry. p. 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Muthiah, S. (7 September 2009). "The pioneer 'Tamil' film-maker". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Thoraval, Yves; Thoraval, Yves (2007). The cinemas of India (Repr ed.). Delhi: Macmillan India. ISBN 978-0-333-93410-4.

- ^ "Metro Plus Chennai / Madras Miscellany: The pioneer 'Tamil' film-maker". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ Burra & Rao, 252–253

- ^ Purohit, Vinayak (1988). Arts of transitional India twentieth century, Volume 1. Popular Prakashan. p. 985. ISBN 978-0-86132-138-4. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ [Narayanan, Arandhai (2008) (in Tamil) Arambakala Tamil Cinema (1931–1941). Chennai: Vijaya Publications. pp. 10–11. ISBN].

- ^ "Tollywood turns 85: With the release of Bhakta Prahlada, this is how the industry was born". 6 February 2017.

- ^ Narasimham, M. L. (7 November 2010). "SATI SAVITHRI (1933)". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Bhagwan Das Garg (1996). So many cinemas: the motion picture in India. Eminence Designs. p. 86. ISBN 81-900602-1-X.

- ^ "Nagaiah – noble, humble and kind-hearted". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 8 April 2005. Archived from the original on 25 November 2005.

- ^ "Paul Muni of India – Chittoor V. Nagayya". Bharatjanani.com. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ Gokulsing, K.; Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian popular cinema: a narrative of cultural change. Trentham Books. p. 24. ISBN 1-85856-329-1.

- ^ "The Hindu News". The Hindu. 6 May 2005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f Burra & Rao, 254

- ^ "First Indian Colour Film". Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "A revolutionary filmmaker". The Hindu. 22 August 2003. Archived from the original on 17 January 2004. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "He brought cinema to South". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 30 April 2010. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Citation on the participation of Sant Tukaram in the 5th Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematographica in 1937". National Film Archive of India. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "How free is freedom of speech?". Postnoon. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Celebrating 100 Years of Indian Cinema: www.indiancinema100.in". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ a b Rajadhyaksa, 679

- ^ Rajadhyaksa, 681

- ^ Rajadhyaksa, 681–683

- ^ "BAM/PFA - Film Programs". Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Critics on Ray - Satyajit Ray Film and Study Center, UCSC". Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Satyajit Ray: five essential films". British Film Institute. 12 August 2013.

- ^ K. Moti Gokulsing, K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sharpe, Jenny (2005). "Gender, Nation, and Globalization in Monsoon Wedding and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge". Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism. 6 (1): 58–81 [60 & 75]. doi:10.1353/mer.2005.0032. S2CID 201783566.

- ^ Gooptu, Sharmistha (July 2002). "Reviewed work(s): The Cinemas of India (1896–2000) by Yves Thoraval". Economic and Political Weekly. 37 (29): 3023–4.

- ^ a b K. Moti Gokulsing, K. Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham Books. p. 18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rajadhyaksha, Ashish (2016). Indian Cinema: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780191034770.

- ^ a b Maker of innovative, meaningful movies. The Hindu, 15 June 2007

- ^ Ghatak, Ritwik (2000). Rows and Rows of Fences: Ritwik Ghatak on Cinema. Ritwik Memorial & Trust Seagull Books. pp. ix & 134–36.

- ^ Hood, John (2000). The Essential Mystery: The Major Filmmakers of Indian Art Cinema. Orient Longman Limited. pp. 21–4. ISBN 9788125018704.

- ^ "Do Bigha Zamin". Dear Cinema. 3 August 1980. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ Rajadhyaksa, 683

- ^ Sragow, Michael (1994). "An Art Wedded to Truth". The Atlantic Monthly. University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ "Subrata Mitra". Internet Encyclopedia of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Nick Pinkerton (14 April 2009). "First Light: Satyajit Ray From the Apu Trilogy to the Calcutta Trilogy". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ Pani, S. S. (1954). "India in 1953". The Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures. Vol. 36. John W. Alicoate. p. 930.

THE INDIAN FILM INDUSTRY, said to be the second largest in the world, claims to have invested Rs. 420 million and to have a gross annual income of Rs. 250 million.

- ^ a b Rajadhyaksa, 684

- ^ Narasimham, M. L. (16 March 2013). "'Malleeswari' (1951)". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1998) [1994]. Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 323. ISBN 0-19-563579-5.

- ^ Sridharan, Tarini (25 November 2012). "Mother India, not Woman India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Bollywood Blockbusters: Mother India (Part 1) (Documentary). CNN-IBN. 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (23 August 2002). "Mother India (1957). Film in review; 'Mother India'". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ Teo, Stephen (2017). Eastern Westerns: Film and Genre Outside and Inside Hollywood. Taylor & Francis. p. 122. ISBN 9781317592266.

- ^ a b Ganti, Tejaswini (2004). Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. Psychology Press. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-415-28854-5.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (2005). "Chapter 6: Reincarnation". The woman who pretended to be who she was: myths of self-imitation. Oxford University Press. pp. 112–136 [135].

- ^ Usman, Yasser (16 January 2021). "Dilip Kumar as 'Pyaasa' hero is what Guru Dutt wanted. But first day of shoot changed it all". ThePrint. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ "How Bollywood legend Dilip Kumar became India's biggest star". Gulf News. 9 December 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ Mazumder, Ranjib (11 December 2015). "Before Brando, There Was Dilip Kumar". TheQuint. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ Santas, Constantine (2002). Responding to film: A Text Guide for Students of Cinema Art. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8304-1580-9.

- ^ Kevin Lee (5 September 2002). "A Slanted Canon". Asian American Film Commentary. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- ^ a b Totaro, Donato (31 January 2003). "The "Sight & Sound" of Canons". Offscreen Journal. Canada Council for the Arts. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Sight and Sound Poll 1992: Critics". California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ Aaron and Mark Caldwell (2004). "Sight and Sound". Top 100 Movie Lists. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Sight and Sound 1992 Ranking of Films". Archived from the original on 22 October 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ "Sight and Sound 1982 Ranking of Films". Archived from the original on 22 October 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ "2002 Sight & Sound Top Films Survey of 253 International Critics & Film Directors". Cinemacom. 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Sivaji Ganesan's birth anniversary". The Times of India. 1 October 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ Gokulsing & Dissanayake, 132–133

- ^ Kasbekar, Asha (2006). Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. ABC-CLIO. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-85109-636-7.

- ^ Films in Review. Then and There Media, LCC. 1986. p. 368.

And then I had forgotten that lndia leads the world in film production, with 833 motion pictures (up from 741 the previous year).

- ^ "Business India". Business India (478–481). A. H. Advani: 82. July 1996.

As the Indian film industry (mainly Hindi and Telugu combined) is one of the world's largest, with an estimated viewership of 600 million, film music has always been popular.

- ^ "Bollywood: Can new money create a world-class film industry in India?". Business Week. 2 December 2002. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ Lorenzen, Mark (April 2009). "Go West: The Growth of Bollywood" (PDF). Creativity at Work. Copenhagen Business School.

- ^ Rajadhyaksa, 685

- ^ a b c d Rajadhyaksa, 688

- ^ "Salim-Javed: Writing Duo that Revolutionized Indian Cinema". Pandolin. 25 April 2013. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (1 October 2015). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin UK. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ^ a b c d e Raj, Ashok (2009). Hero Vol.2. Hay House. p. 21. ISBN 9789381398036.

- ^ a b "Revisiting Prakash Mehra's Zanjeer: The film that made Amitabh Bachchan". The Indian Express. 20 June 2017.

- ^ Ganti, Tejaswini (2004). Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. Psychology Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780415288545.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (2015). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin Books. p. 72. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ^ a b Kumar, Surendra (2003). Legends of Indian cinema: pen portraits. Har-Anand Publications. p. 51.

- ^ a b Mazumdar, Ranjani (2007). Bombay Cinema: An Archive of the City. University of Minnesota Press. p. 14. ISBN 9781452913025.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (2015). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin Group. p. 74. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ^ a b "Deewaar was the perfect script: Amitabh Bachchan on 42 years of the cult film". Hindustan Times. 29 January 2017.

- ^ Amitava Kumar (23 December 2008). "Slumdog Millionaire's Bollywood Ancestors". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ Anand (7 March 2004). "On the Bollywood beat". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 3 April 2004. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ Subhash K Jha (8 April 2005). "Amit Khanna: The Man who saw 'Bollywood'". Sify. Archived from the original on 9 April 2005. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Chaudhuri, Diptakirti (1 October 2015). Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin UK. p. 58. ISBN 9789352140084.

- ^ "How film-maker Nasir Husain started the trend for Bollywood masala films". Hindustan Times. 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b Kaushik Bhaumik, An Insightful Reading of Our Many Indian Identities, The Wire, 12 March 2016

- ^ Rachel Dwyer (2005). 100 Bollywood films. Lotus Collection, Roli Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7436-433-3. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ iDiva (13 October 2011). "Sridevi – The Dancing Queen". Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Ray, Kunal (18 December 2016). "Romancing the 1980s". The Hindu.

- ^ Arundhati Roy, Author-Activist Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine india-today.com. Retrieved 16 June 2013

- ^ "The Great Indian Rape-Trick" Archived 14 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, SAWNET – The South Asian Women's NETwork. Retrieved 25 November 2011

- ^ "From India Today Magazine | When Sridevi emerged as the highest paid Indian actress". India Today. 30 June 1987. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Aruti Nayar (16 December 2007). "Bollywood on the table". The Tribune. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ Christian Jungen (4 April 2009). "Urban Movies: The Diversity of Indian Cinema". FIPRESCI. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ "Masand's Verdict: Contract, mangled mess of Satya, Company". CNN-News18.

- ^ "Behind The Scenes - Rachel Dwyer - May 30, 2005". outlookindia.com.

- ^ "The Sunday Tribune - Spectrum". tribuneindia.com.

- ^ "100 Years of Indian Cinema: The 100 greatest Indian films of all time". IBNLive. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ a b "The Three Khans of Bollywood – DESIblitz". 18 September 2012.

- ^ Cain, Rob. "Are Bollywood's Three Khans The Last Of The Movie Kings?". Forbes.

- ^ Raghavendra, MK (16 October 2016). "After Aamir, SRK, Salman, why Bollywood's next male superstar may need a decade to rise". Firstpost. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Why Aamir Khan Is The King Of Khans: Foreign Media". NDTV. Agence France-Presse. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ D'Cunha, Suparna Dutt. "Why 'Dangal' Star Aamir Khan Is The New King Of Bollywood". Forbes.

- ^ Cain, Rob (5 October 2017). "Why Aamir Khan Is Arguably The World's Biggest Movie Star, Part 2". Forbes.

- ^ Muzaffar Raina (25 November 2013). "Protests hit Haider shoot on Valley campus". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ Kishore, Vikrant; Sarwal, Amit; Patra, Parichay (2016). Salaam Bollywood: Representations and Interpretations. Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 9781317232865.

- ^ Jha, Lata (18 July 2016). "10 Rajinikanth films that were remakes of Amitabh Bachchan starrers". Mint.

- ^ "Mayabazar (1957)". The Hindu. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ ""1" The Hindu". The Hindu. 9 February 2013.

- ^ "100 Years of Indian Cinema: The 100 greatest Indian films of all time". 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ "Mayabazar' is India's greatest film ever: IBNLive poll". 12 May 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "K. Viswanath Film craft Page 6 DFF" (PDF). Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Prasad, Shishir; Ramnath, N. S.; Mitter, Sohini (27 April 2013). "25 Greatest Acting Performances of Indian Cinema". Forbes. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ "Dance without frontiers: K Viswanath – Director who aims to revive classical arts". 2 May 2017.

- ^ 30 June 2011 - Ranjana Dave (30 June 2011). "The meaning in movement". The Asian Age. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Arts / Cinema: Conscientious filmmaker". The Hindu (Press release). 7 May 2011. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Tikkavarapu Pattabhirama Reddy – Poet, Film maker of international fame from NelloreOne Nellore". 1nellore.com. One Nellore. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "MEDIAWAVE ARCHÍVUM (1991-2022) :: 1992 :: FILMES DÍJLISTA - www.mediawave.hu". mwave.irq.hu.

- ^ "Narsing Rao's films regale Delhi" (Press release). webindia123.com. 21 December 2008. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Metro Plus Hyderabad / Travel : Unsung moments". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 March 2005.

- ^ "Awards". Busan International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "How Kamli came alive onscreen". Rediff.com (Press release). 31 December 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Vanaja Best First Feature". 57th Berlinale. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (19 December 2012). "The year's ten best films and other shenanigans | Roger Ebert's Journal". Roger Ebert. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Raghavan, Nikhil (4 October 2010). "A saga in the making?". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Pasupulate, Karthik (29 October 2015). "Raj Tarun to star in a silent film by RGV". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Nagarjuna's Shiva completes 25 years". The Times of India. 5 October 2014. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Cannes critic on RGV's film craft at fribourg festival". Indiatoday.in. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Gopalrao, Griddaluru (18 October 1991). "చిత్ర సమీక్ష: క్షణ క్షణం" (PDF). Zamin Ryot (in Telugu). p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Narasimham, M. L. (12 October 2018). "The story behind the song ' Nerajaanavule' from the movie Aditya 369". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "Singeetam Srinivasa Rao Interview: "The Golden Rule Of Cinema Is That There Is No Golden Rule"". Silverscreen.in. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ Srinivasan, Pavithra (7 September 2010). "Singeetham Srinivasa Rao's gems before Christ". Rediff.com. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ "Sudeep's excited about film with Ram Gopal Varma". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Kondaveeti Donga (1990)". IMDb.[dead link]

- ^ Gopalan, Krishna (30 August 2008). "Southern movie stars & politics: A long love affair". The Economic Times. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ Gangadhar, V (17 July 2000). "rediff.com, Movies: The Dollar Dreams review". Rediff.com. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Kalyanam, Rajeswari (24 October 2015). "Breaking new grounds". The Hans India. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ Sharma, Suparna (30 April 2022). "Indian director Rajamouli scores a global hit with new film RRR".

- ^ Dwyer, Rachel (1 April 2022). "Director's Roar".

- ^ "The secret of the pan-Indian success of films from the south: Balancing the local and universal". 3 August 2022.

- ^ "'Baahubali' nominated for Saturn Awards in five categories". 27 February 2016.

- ^ ""Baahubali-the-beginning"". Metacritic. 9 September 2022.

- ^ McNary, Dave (27 June 2018). "'Black Panther' Leads Saturn Awards; 'Better Call Saul,' 'Twin Peaks' Top TV Trophies". Variety. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Sudhir, TS (May 2017). "Is Baahubali 2 a Hindu film? Dissecting religion, folklore, mythology in Rajamouli's epic saga". FirstPost. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ "'RRR' Oscar campaign gets a boost: Rajamouli's film named among National Board of Review's 10 best films". The Economic Times. 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Oscars 2023: RRR's Naatu Naatu wins best original song". 13 March 2023.

- ^ Davis, Clayton (12 December 2022). "'RRR' Roars With Golden Globe Noms for Original Song and Non-English Language Film".

- ^ ""Is Prabhas India's First Legit PAN Indian Star?'"". 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Bollywood's Telugu takeover: 'Shehzada' to 'Jersey', remakes of hit South films". The Times of India. 18 February 2023. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ "The Tamil Nadu Entertainments Tax Act, 1939" (PDF). Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Pillai, Sreedhar. "A gold mine around the globe". The Hindu. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Eros buys Tamil film distributor". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- "With high demand for Indian movies, Big Cinemas goes global". The Times of India. 12 June 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ "Symposium: Sri Lanka's Cultural Experience". Frontline. Chennai, India. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Celebration of shared heritage at Canadian film festival". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 August 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Baskaran, Sundararaj Theodore (2013). The Eye Of The Serpent: An Introduction To Tamil Cinema. Westland. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-93-83260-74-4.

- ^ Movie Buzz (14 July 2011). "Tamil films dominate Andhra market". Sify. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "A few hits and many flops". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 December 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2007.

- ^ "Mutu: Odoru Maharaja" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Gautaman Bhaskaran (6 January 2002). "Rajnikanth casts spell on Japanese viewers". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Agni Natchathiram & Kaakha Kaakha | 12 Unknown facts in Kollywood history!". Behindwoods. 11 March 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "India's Oscar failures (25 Images)". Movies.ndtv.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Nayakan, All-Time 100 Best Films, Time, 2005

- ^ "Cinema History Malayalam Cinema". Malayalamcinema.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ "The Movie Interview: Adoor Gopalakrishnan". Rediff. 31 July 1997. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Throne of Death". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ^ "Rediff On The NeT, Movies: An interview with Murali Nair". M.rediff.com. 8 July 1999. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Marana Simhasanam (1999)". BFI. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ site admin (7 June 1999). "Golden windfall - Society & The Arts News - Issue Date: Jun 7, 1999". Indiatoday.in. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Osella, Filippo; Osella, Caroline (2000). Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict. Pluto Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-7453-1693-X.

- ^ Mathews, Anna. "Shobana reminisces on impact of Manichitrathazhu on film's "27 birthday"". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "Wu Sha: The Chinese remake of Mohanlal starrer Drishyam is minting moolah". The Indian Express. 22 January 2020.

- ^ @antonypbvr (16 September 2021). "ഇൻഡോനേഷ്യൻ ഭാഷയിലേക്ക് റീമേക്ക് ചെയ്യുന്ന ആദ്യ മലയാള ചിത്രമായി 'ദൃശ്യം' മാറിയ വിവരം സന്തോഷപൂർവം അറിയിക്കുന്നു. ജ..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Mohanlal's 'Drishyam' to be remade in Indonesian". The Times of India.

- ^ "Tikkavarapu Pattabhirama Reddy – Poet, Film maker of international fame from Nellore". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "TS Nagabharana movies list". bharatmovies.com. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ "Asiatic Film Mediale". asiaticafilmmediale.it. Archived from the original on 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Girish Kasaravalli to be felicitated". The Hindu. 25 April 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "A genius of theatre". The Frontline. 25 October 2002. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Mitra, Shilajit (5 December 2018). "The story of KGF is fresh and special for Indian cinema: Yash". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "KGF Chapter 2 Closing Collections : యశ్ కేజీఎఫ్ ఛాప్టర్ 2 క్లోజింగ్ కలెక్షన్స్.. ఎన్ని వందల కోట్ల లాభం అంటే". 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Yash's KGF: Chapter 2 makes multiple records in Canada". Asianet News Network Pvt Ltd. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Yash's film KGF: Chapter 1 made more than Rs 250 crore at the box office worldwide and became a magnum-opus. Now, the makers are busy with pre-production work of KGF: Chapter 2.", indiatoday, 9 February 2019

- ^ "Kantara Twitter review: Celebs and netizens hail Rishab Shetty's film as a masterpiece". Ottplay. Retrieved 30 September 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Goldsmith, Melissa U. D.; Willson, Paige A.; Fonseca, Anthony J. (7 October 2016). The Encyclopedia of Musicians and Bands on Film. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-6987-3.

![Dadasaheb Phalke, c. 1930s[4][5][6][7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Phalke.jpg/67px-Phalke.jpg)